September 1, 2021

This article examines why a closed-loop root cause analysis (RCA) and corrective and preventive action (CAPA) process is critical, as well as the key steps it should cover. In addition, learn how an enterprise quality management system (EQMS) makes the process more effective, and how to close the loop on a hypothetical use case.

Root Cause Analysis and CAPA: A Use Case

Consider the following hypothetical scenario: During quality control (QC) final product inspection, an inspector opens a sealed, sterile package containing a suture for testing. Upon opening, several black particles fall out on the inspection table. As a result, the inspector records the event on a form to hold that lot and the adjacent lots due to the discovery of the foreign matter.

Subsequently, a trace by lot number uncovers similar black particles piling up on a conveyor belt on the identified production line. The belt is damaged and rubbing the rail, causing it to shred. Immediate corrections include obtaining samples from the conveyor for testing to determine if the particles match the foreign matter in the package and replacing the belt. After a final inspection and cleaning, the equipment can be approved to return to production.

The root cause analysis reveals the belt was knocked out of alignment when a heavy calibration cart accidentally hit the machine frame. The approved corrective action is to install a steel bumper in front of the machine to prevent further contact. An additional corrective action is generated to creating and taping off a dedicated space on the floor to park the cart and installing locking wheels. Finally, operating procedures and related training is amended to update and educate employees how to handle the cart on the production floor.

While many companies might stop here, that would be a mistake. Unfortunately, the corrective actions have only addressed the symptom—not the true root cause. As a result, the issue may not permanently be resolved.

Closing the Loop Is Key

With root cause analysis and corrective action, a closed-loop process means the difference between band-aid fixes and resolving problems. It’s also an area where quality management software is important to link each step together in a defined workflow. Without the continuity of an automated QMS, issues get lost or forgotten if they are only tracked through paper records and email.

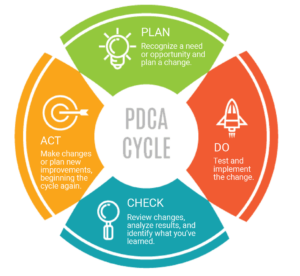

A closed-loop CAPA process closely follows the Plan-Do-Check-Act approach :

Plan:

- Classify event (external vs. internal)

- Assess risk to route for fast-track review (low risk) or full analysis (higher risk)

- Root cause analysis

Do:

- Containment

- Correction action(s)

Check:

- Verification and effectiveness check

Act:

- Make adjustments

- Plan changes if required. (Planning changes repeats the cycle.)

Step 1: Containment & Correction

When an issue is found, the first step is to contain and correct it on the spot when possible. In other words, you’ll want to stop the bleeding while further monitoring the issue.

Tasks at this stage may include, for example:

- Shutting down the line, capturing evidence, and cleaning up the area

- Determining which batches or lots are affected to help with investigations, testing, and risk mitigation

- Notifying team members in quality assurance (QA), QC, and operations

- Identifying, labeling, and separating any affected products for further testing or disposition

- Making corrections needed to return the process back online

- Monitoring performance to verify that the process is working as expected or if it needs to be shut down longer for adjustments

Step 2: Classification and Risk Assessment

The next step is to classify the problem and conduct a risk assessment to determine the appropriate corrective action workflow.

Issues fall into one of two categories:

- External: Product is already outside the company’s control

- Internal: Product is still within the company’s control

Furthermore, you’ll need to decide whether the issue is high-risk or low-risk. High-risk issues are those with a direct patient impact or repeat occurrences requiring full root cause analysis and investigation. Conversely, low-risk issues are those unlikely to impact patients.

Routing low-risk issues to a fast-track process with less documentation, investigation, and verification requirements helps reduce the backlog of corrective actions and administrative burden. While generally internal, fast-track routing can include some external issues that have happened before with a previous documented investigation.

This approach is recommended by the Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC) and FDA as part of their Case for Quality initiative (CFQ), which has done extensive work on corrective action / CAPA process improvement.

Step 3: Root Cause Analysis

Manufacturers use a variety of analysis methods and tools to conduct root cause analysis, including:

- 5 Whys

- 8D

- Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA)

- Fault tree analysis (FTA)

- Fishbone diagrams

- Define, measure, analyze, improve, and control (DMAIC)

- Kaizen

Companies should use what’s appropriate based on the risk of situation and which method works best for the organization. What is most important is not to mistake a symptom for a true root cause. True root cause analysis results in corrective action(s) that prevent recurrence.

Depending on the methods you use, steps in the root cause analysis process may include:

- Problem statement: Identifying and clearly defining the correct problem is a critical first step to developing a permanent solution.

- Brainstorming potential causes: Here, the team may meet to discuss and analyze possible causes. Engineers may review FMEA records, historical knowledge of process and equipment changes, and preventive maintenance records, including part replacements.

- Collecting data: This step includes collecting observational data from the manufacturing line, QC lab inspections, and test results. Other data sources include historical quality data in the EQMS such as complaints, change control records, CAPA, and nonconformances.

- Analyzing data: Data collected is analyzed, using results from different root cause analysis tools to evaluate hypotheses from initial brainstorming meetings and identify the likely root cause(s).

Step 4: Corrective Action

Once you’ve found the root cause of a problem, the next step is creating solutions that will prevent recurrence. Corrective actions may require action items, resources, funding, and approvals from different departments in the company.

Here, there are a few key steps you’ll want to link together within your EQMS:

- Action plans: These should include approved action items with due dates, with monitored assignments for completing the corrective actions. Action plans may require updating documents such as standard operating procedures (SOPs), work instructions, training, engineering change orders (ECOs), and product or material specifications.

- Verification: Here you’ll need to verify that the corrective action was implemented and effectiveness checks are approved and assigned.

- Effectiveness check: Preventing recurrence means monitoring quality reports after a period of time to verify the corrective action is actually working.

Step 5: Preventive Action

While corrective action fixes one instance of a problem, preventive action goes further to prevent it from happening elsewhere. That requires taking lessons learned from an issue and applying them across the plant and the entire organization.

In order to be successful, you’ll need to look for where the problem could happen with similar equipment, situations, or processes.

Root Cause Analysis and CAPA: Use Case Revisited

Based on our earlier scenario with the shredded machine belt, let’s see what a closed-loop process would look like in practice.

The initial root cause analysis reveals the belt was knocked out of alignment when a heavy calibration cart accidentally hit the machine frame. Corrective actions were taken to fix the immediate issue and operating procedures and related training were updated.

However, during further root cause analysis, a consult with engineers determines that the machine frame isn’t designed to withstand an impact from a 200-pound cart. As a result, you implement a new corrective action, an ECO focused on improving the structure and anchoring of the machine frame.

Furthermore, preventive actions called for review of other places where similarly heavy calibration carts travel near machines and strengthening their frames as well. Additional decisions may be evaluated to minimize manual calibration by reducing the need for the cart. For example, the organization may evaluate the cost/benefit of installing industrial internet of things (IIoT) sensors to do automatic calibrations.

Finally, ongoing monitoring and evaluation may lead to updating the PM inspection processes or installing cameras to monitor critical machines and their general areas. Additionally, a change request to the equipment design template would ensure all future lines are made secure according to the new standards.

Taken together, this is a complex process involving multiple people and approvals. Working with paper or email would undoubtedly extend the process, allowing problems to persist longer, and quality to degrade further.

Conclusion

When a root cause analysis is done, it’s not over. Create an actionable outline of tasks for review over time to close the loop and continue quality improvement. Also, review your documented root cause analysis process at determined intervals to confirm it works across the organization. Remember, what works in one area may not be effective in another.

Finally, consider the benefits of a configurable EQMS. An automated system creates agile workflows based on internal approval processes, business rules, and other requirements. Furthermore, it provides an auditable record of quality issues and documented proof of using risk-based thinking—and the ability to sleep at night knowing a process is more robust.

RELATED READING: Human Error is a Precipitator for Root Cause Analysis, Not Blame