March 8, 2021

For decades, pharmaceutical and medical device companies have operated under the assumption that they must document and validate each and every software used in their processes. The concern was that if they didn’t, they would be at higher risk for potential audit observations and 483 warning letters.

This approach to computer systems validation (CSV) aims to ensure compliance with 21 CFR Part 820.75, which relates to process validation. Unfortunately, the unintended result has been a slow adoption of technology software solutions that improve efficiency, product quality, and patient outcomes.

Enter computer systems assurance (CSA), a risk-based, least burdensome approach to streamline validation based on the International Society of Pharmaceutical Engineers (ISPE) GAMP® 5 model.

GAMP 5 guidance for process validation recognizes different types of software based on the core design and technical skills for sustainability. The model encourages manufacturers to implement new technologies to achieve efficiency gains and quality improvements.

This article compares CSV and CSA, how companies benefit from the paradigm shift, as well as validation elements to look for when selecting non-manufacturing software solutions.

CSV vs. CSA: What’s the Difference?

Computer software validation (CSV) as defined by the FDA is a documented process to demonstrate that computer software works according to its intended design. Computer software assurance (CSA) is a risk-based approach that limits testing to functions directly impacting product quality and patient safety. CSA also encourages companies to use the software vendor’s documentation to reduce the testing burden and deploy applications faster.

According to the FDA, software not used in a product (e.g., off-the-shelf production manufacturing software) is not subject to the same rigorous requirements of computer systems validation that have been used in process validation. Instead, manufacturers can use computer systems assurance to target verification and validation testing for only high-risk activities.

The FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) has prioritized guidance on CSA for QMS software for publication in 2021 or 2022. It will provide specific guidelines to define CSA and provide direction for making this transition.

The Challenge of Computer Software Validation

Encouraging investment in technology is a priority for the FDA as it acknowledges digital transformation as a catalyst for reducing quality issues and patient risk. Conversely, the agency’s Case for Quality initiative to identify the practices of high performers in the medical device industry, identified software validation as a leading roadblock to technology adoption.

Unfortunately, the industry misinterpreted 21 CFR Part 820.75 process validation and applied those requirements to software used in a life science company. Manufacturers in turn subjected all software used in their processes—from software as a medical device (SaMD) to document management software—to extensive validation testing.

The unintended consequence was steep computer software validation implementation and change management costs. The prohibitive costs often meant life sciences companies avoided technology investments altogether—the exact opposite of what the FDA is trying to promote.

Computer Systems Assurance: A Risk-Based Approach

CSA involves applying different degrees of validation testing according to the risk associated with the software. CSA can be broken down into four broad steps:

- Identify the intended software use.

Does the software impact product quality or patient safety? If not, you don’t need the same level of assurance as with software that impacts the product or patient safety. For example, software such as document management, change management, and audit management doesn’t require the same level of testing as software within a device. - Determine areas or functions that can impact product quality, patient safety, or system integrity.

Computer systems validation focuses on calculating the severity of impact and probability of failure, leading to a prioritization of risk. The recommended process with computer systems assurance, however, is calculating the risk/impact on patient safety and product quality, as well as the implementation method of the software functionality.Figure 1: Sample risk-based impact score based on the type of implementation method.

Figure 2: Computer software implementation definitions.

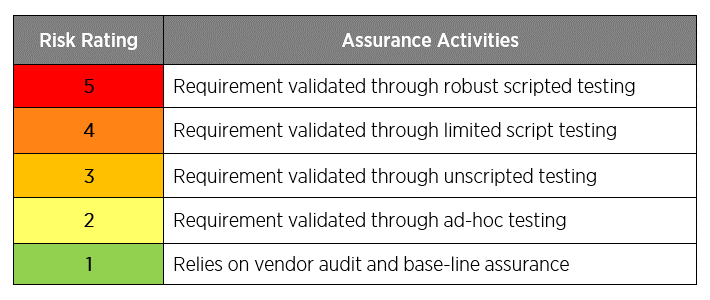

Figure 3: Validation assurance activities and related risk ratings.

- Leverage vendor documentation where possible.

Companies shouldn’t waste time reproducing audited vendor documentation and validation. If the vendor has quality documentation and validation in place, use it. - Conduct scripted and unscripted testing activities as needed based on risk.

Using a risk-based approach requires experts to understand business processes and evaluate the system’s functionality to get more value from their software.

Unscripted testing is used on lower-risk systems that do not directly impact the product or patient safety. Detailed test scripts aren’t needed, but companies should document a test objective and pass/fail results.

Scripted testing is for higher-risk systems that directly impact the product or patient safety. The traditional step-by-step procedure with expected results and pass/fail should be documented.

What the Transition to Computer Systems Assurance Means for the QMS

In terms of QMS software, which is not part of the product, the risk to product quality and patient safety is far lower and therefore does not require the same level of testing. GAMP 5 guidance acknowledges the evolution of industry software, recognizing distinct levels of risk associated with different types of software. The most popular industry software category is Category 4 configured software, which allows companies to use a set of verified tools to make software changes without coding to meet business process needs and requirements.

In other words, the shift to CSA saves time, money, and resources. You don’t need to document and perform full validation for out-of-the-box software that’s already been done by the software vendor.

Here’s a practical example: While manufacturers should test critical elements such as user access roles, that does not necessarily require generating a 100-page test script. Instead, companies can leverage the supplier’s testing and verify the functionality in an end-to-end use case test scenario. In this situation, screen captures are enough to provide evidence that the software works as intended.

Benefits of CSA over CSV

Moving from traditional CSV to CSA represents a cultural paradigm shift concerning validation, slashing the documentation, project timelines, and costs for life science companies implementing software.

In a December 2020 Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC) Case for Quality Forum, the FDA and industry partners highlighted the results companies have achieved with this approach, including:

- 90% or more reduction in test script and tester errors

- Validation time cut 50% or more, with faster implementation as a whole

- Lower overall project cost

- Higher morale, quality, and productivity

- More time for critical thinking as opposed to generating documentation

QMS Validation Services: What to Look For

It’s important to note that the right level of documentation is still necessary to avoid regulatory scrutiny. Follow the FDA audit perspective of, “If it’s not documented, it didn’t happen.”

In terms of QMS software, companies should look for the supplier’s out-of-the-box (OOB) technical and documentation that includes:

- User/functional requirement specification

- Risk assessment

- Functional design specification

- Requirement traceability

- Reusable operational qualification (OQ)

- Reusable performance qualification (PQ)

- Validation summary report

The QMS should also come with technical and validation document templates that can be customized for your configured QMS, including templates for:

- User/functional requirement specification

- Risk assessment

- Functional design specification

- Requirement traceability

- Configuration document

- Operational qualification (OQ)

- Performance qualification (PQ)

Automated validation is also a must for simplifying test management within configured solutions, allowing companies to deploy solutions faster while keeping the QMS in a state of control.

Finally, it’s important to ask questions about how professional services and validation services teams work together. Avoiding delays and costs requires a collaborative handoff between the two, with validation services part of the process from the beginning (even during project quoting).

The transition from computer systems validation to computer systems assurance is underway, and companies are already starting to see the benefits in terms of time and cost during software implementations. By enabling a risk-based approach using critical thinking, the FDA hopes to grow the adoption of technology that benefits patients, including QMS, product lifecycle management (PLM), laboratory information management system (LIMS) software, and more.

CSA does not replace CSV, nor does it contradict it. Instead, they need to coexist and be used appropriately. CSA is a simplified strategy for achieving CSV, allowing companies to spend more time testing systems based on risk than creating documentation—with better results to show for it.

Related resources:

- MDIC, Case for Quality forum presentation

- USDM Life Sciences, Q&A: CSV, CSA and Why the Paradigm Shift

- ValGenesis, How to Accelerate Adoption of FDA’s Computer Software Assurance